Schulz + Allen Clarke

A leader in natural horsemanship, Allen Clarke shares the necessary work to adopt horse reasoning, establish sanctuary, and reward thought—not action—in our horses.

As Allen Clarke tells it, an early encounter with a miniature horse left him in tears. “At 12-years-old I was put on this little Shetland pony,” Clarke notes in his jocular Australian accent, “and I cried my eyes out in fear.” It was something of an ignominious start for the young Clarke who grew up in a household of tried-and-true horsemen — Allen’s great-grandfather captured wild horses, training them for the Australian calvary, while his father, Reg Clarke, broke the first Australian horse to arrive in America. And yet, by the age of 15, the younger Clarke was riding horses that most others found difficult to. “I think the real reason I stuck with it,” Clarke puckishly admits, “is that my father really respected horse experts — I figured if I could do the horses that no one else could do, that would make me the horse expert and then I would get my daddy's love.”

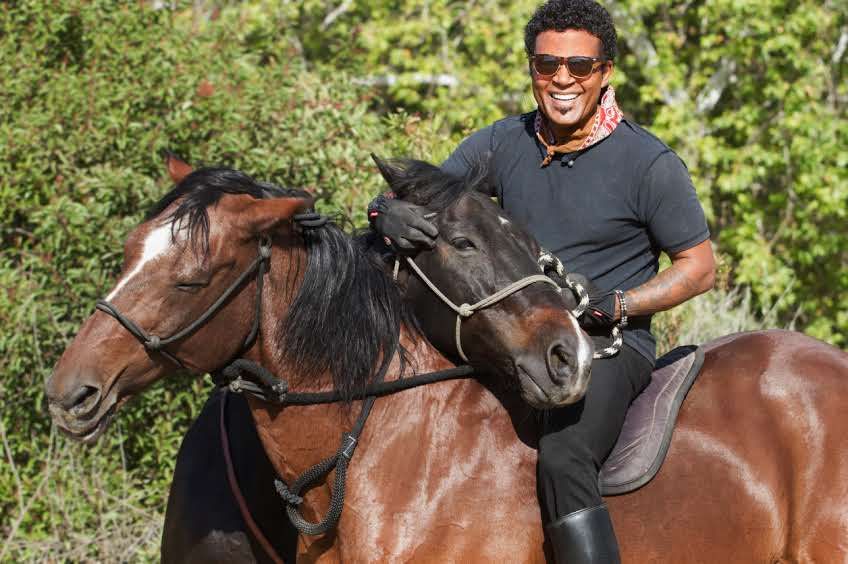

Familial reasons aside, Clarke, now 62-years-old, is recognized as one of today’s leading experts when it comes to rehabilitating difficult and dangerous horses. From Horsemanship Unlimited, his 8-acre ranch located amidst the lush vineyards and rolling hills of Temecula in Southern California, Clarke employs the eponymously titled “Allen Clarke Technique,” a process that has earned him the respect of a high-profile, if not decidedly discrete clientele. Featuring a round pen where Clarke’s initial groundwork begins, the ranch also includes a dressage arena and several smaller arenas designed with obstacles — from jumps and fluttering signs to a life-sized fake cow — to address a wide range of animal behaviors.

With more than 40 years of experience under his belt, Clarke has come to believe that the issues he encounters in the horses he works with stem from an “anthropomorphic conditioning” which runs counter to their nature. “Horses in nature learn discipline, starting from their mothers,” Clarke points out, adding that behavioral issues can begin to manifest when a “foal is taken out of that setting” and subjected to human-oriented conditioning that it cannot comprehend. In other words, Clarke explains, “people project their emotions onto a horse, believing ‘If I understand it, it must be simple.’” For Clarke, most riders expect horses to think and rationalize like humans, rather than attempt to frame their interactions from the perspective of the horse. That failure to “think like a horse,” Clarke adds, results in the “man-made glitches” — the behavioral problems — that he is brought on to correct. As Clarke points out, to work with horses, “you have to have horse reasoning.”

And yet, most horse owners and riders, Clarke observes, do not possess an awareness or facility to communicate with their horses because they are unprepared — or unwilling — to put in the amount of time required to do so. “People have a relationship with a dog that lives in their house,” he points out, adding, “then they interact with a horse for about an hour and wonder why the horse doesn’t have the same connection that a dog has.” Growing up in Australia, Clarke notes, owning a horse meant constant, daily contact between rider and horse, a dynamic that was more in-tune with the needs of the animal. “When I was young, every girl in the country rode her horse bareback with a snaffle bit,” he recalls. “When they went anywhere, they just jumped on the horse, rode it up the road amid all the traffic.”

In the end, Clarke notes, many riders are unable to “understand” what their horse is trying to “tell” them. This failure, paired with conditioning that is contrary to a horse's nature, results in the behavioral issues that Clarke works to resolve.

To be sure, Clarke’s assessment of his industry is unflattering and one likely to raise more than a few hackles, so to speak. In Clarke’s eyes the majority of those who are working with horses today are what he refers to as “horse conditioners.” As he sees it, the reason for this is clear: “horse trainers aren't here to educate the horses. They're here to sell the horse.” Speaking of the conditioning of horses for big-tickets sales, Clarke is characteristically frank: “The money is in winning the Grand Prix. The money is in selling the horse to the neighbor or to the new client, to someone internationally.” From his perspective, the profession has evolved to where it is easier — and more immediately financially rewarding — to condition horses for a quick sale. “When they prepare horses,” for sale, Clarke points out, they condition the horse to act and appear trained: “they do a straight line somewhere. The horse is doing a beautiful trot. The horse is doing a beautiful canter.” But, as Clarke is quick to note, “three weeks down the line,” the new owners soon discover their horses haven’t been properly trained, just conditioned for sale. And, when a behavioral issue with the horse develops, Clarke notes, these “conditioners” lack the knowledge and ability to correct them.

Not surprisingly, seeking a fix to the solution, Clarke finds himself regularly approached by other trainers who are desperate to resolve these issues on the part of the horse’s owners — their customers. “99% of my business,” Clarke notes, “comes from Olympic, professional, successful, clever, business horse training.” In comparison to what Clarke charges for his services, those who sell horses stand to make a more sizeable profit. “I had one rider that sent me six horses this year,” Clarke notes, “and he said: ‘Why wouldn't I give you 10 grand to fix this horse? I can sell it and make a $70,000 profit. Take out your 10, that's 60 grand in my pockets.’” Indeed, as Clarke surmises, “you know what skill he’s learning: how to sell that horse to those people.”

An important first step when a horse arrives is to establish what Clarke refers to as a sense of “sanctuary” for the animal. “Sanctuary can be simply to look at me, to give me eyes, acknowledge that I’m here,” Clarke noted in a 2014 interview with Untacked magazine. It's at this point, once eye contact has been made, that Clarke ascertains the kind of horse he’s dealing with. “The first thing I'd look at is their eyes to see what expressions they have,” he notes, “and 99% of the time I get only one or two expressions.”

The first expression, explained by Clarke with his unmistakable style of folksy Australian common sense, is what he refers to as “I'm Looking Up Over the Fence.” For Clarke, this expression relays a particular mindset for a horse that, could it speak, would say: “I've tried to communicate with you since the first time you've touched me, and the only way I know around this, you nagging pile of garbage, is to ignore you.” The other expression is what Clarke fittingly calls “The Shark Week Eye” (a reference to the Discovery Channel’s popular annual wildlife TV series). “You know the scene when the shark’s just about to bite you and it rolls its eye back and all you see is the anger and hatred in it? Well we can get those with our horses, too.” From here, Clarke takes the first important steps in his process for rehabilitating horses.

I’ve got to get them looking to me for answers. You have to be the leader for the horse.

Next, according to Clarke, is to get the horse to put its head down. “For a horse to put its head down is a very big act of acceptance and submission,” he points out, adding, “I put them down in that position for two reasons: First, by demanding it, they start to believe that I am the leader. Second, if I don't break that trust for them, if every time they do as I ask them — including putting themselves in a passive position — they come to believe they are protected.” Importantly, too, Clarke notes, conditioning the horse to put its head down upon command acts as a sort of reset should it become agitated or distressed. “I want a shut off switch,” Clarke points out: “if the horse gets to panicking, I've got to go back to a ground zero to where we can go, ‘Okay, take a deep breath. You'll be okay.’”

From there, Clarke begins conditioning the horse through a series of movement-specific exercises. “I have to be able to move the six parts of their body — their nose, throat latch, neck, rib, shoulder, and hip,” he explains, underscoring the importance of the isolation-specific technique: “If I can't maneuver each one of those body parts, I'm not getting on it.”

Another important aspect of Clarke’s approach to rehabilitating a horse is recognizing when to stop. But the concept of “when to stop,” Clarke underscores, is a multi-layered and vital technique to horse training, one that involves two key elements: rewarding the horses thought, not action, and recognizing the point at which the rider needs to cease certain behaviors toward the horse. On the first point, Clarke explains, “If you give the cue and the horse is about to make the maneuver you want — you have to stop.” Explaining his thinking further, Clarke continues, “Reward the horse when it's about to make an intention of the right move,” he adds, “not after it's made the right move because then your timing is so far out.”

As for the second aspect of when to stop — on the part of the rider — Clarke calls out repetitive training and practices that adversely affect a horse’s mental state. Speaking with his hallmark no-holds-barred grit Clarke notes, “there are certain disciplines that practice until the horse hates it,” disciplines that, in his mind, are akin to “Chinese water torture” for a horse. From the horse’s point of view, Clarke contends, “if you just keep hammering me and hammering me and hammering me mentally, I'm going to start rearing. I'm going to start grinding the bit. I'm going to start swishing my tail. You know how come? Because I can't make you happy no matter what I frigging do.” Indeed, for Clarke, stopping is also understanding when to resist the urge to train a horse. “All the horse is looking at us for,” he notes, “is the path of least resistance — all he’s looking for is how to get you to stop.”

Ultimately, for Clarke, however, the process of rehabilitating a horse is not about establishing control of it, but rather implementing a relationship based on release. “Your relationship with a horse,” Clarke notes, “should be recalled the ‘releasemanship.’” As Clarke points out, for a rider to succeed with their mount, “It's when you release that matters.”